|

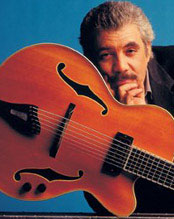

Jimmy Bruno |

Bio

Guitarist

Arranger

Conductor

Listen

Gallery

Fun Stuff

Contact

Originally published in the November, 1995 issue of the newsletter of the Cincinnati Jazz Guitar Society.

Jimmy Bruno has as much to say with words as he does with his music. One simple question sparks an extended response that shows great refinement of thought. On several topics, he shows us his growth as a person and a player as he indicates how his thoughts changed through the years.

|

|

Jimmy Bruno |

Born July 22, 1953, in Philadelphia, Bruno started learning to play guitar at age 7 from his father. He began playing professionally right after high school and his first big professional gig came at age 19, when he went on the road with Buddy Rich. For several years, he lived in Las Vegas and Los Angeles, playing commercial music. He made a good living but was unsatisfied musically during this period.

He now lives back in Philadelphia with his wife and 2 daughters, and is a close friend of fellow Philadelphia guitarist Pat Martino, whom Bruno calls an "inspiration."

In 1992, Concord released his first jazz recording, "Sleight of Hand," which was followed in 1994 by "Burniní," and many more since.

TB: Were you always really good?

JB: I guess, yeah. I would have to say yeah. It came real easy. I learned how to play and got a lot of technique from studying violin books. I spent a lot of time learning the neck of the guitar. I used to practice about 8 hours a day. The real intensive practicing started when I was about 16. Before that it was about 2, 3 hours, and when I was a kid maybe an hour a day. I liked it, so whenever I had some spare time, I would be playing.

TB: I read that you never went through the rock and roll phase.

JB: No. I never really went through that. My father was a musician and my mother was a singer, and they always liked jazz so they put down all that stuff. So I knew that the music was dumb before I was able to figure it out on my own.

TB: What was your first guitar?

JB: I was like 8 or 9 and my father had bought me a Gibson L4. It was a fat body guitar, and I didnít like it. So he took it back and got a white solid body guitar called a Supro. They were real cheap and it was a real piece of shit. But I had this great guitar and I didnít want it because it didnít look like what the other kids had so I wanted to have a piece of shit. (Laughter) Now I wish I had that other guitar.

TB: Iím curious about your transition from the commercial world to the jazz world.

JB: Let me back up a bit. When I got out of high school, all I wanted to do was play jazz. And I kind of did that for a couple years. It was real hard to get anything going. So I went on the road with the Buddy Rich band when I was 19. When I came off the road I tried to do jazz again but there wasnít any work and I got tired of living really poor. So I went to Las Vegas. I played for all the dumb acts out there. I got really sick of that. There was no jazz there.

So I moved to L.A. I figured, well at least Iíll only have to play the music once in the studio. You play it one time and you never play it again. Well, that didnít work out either. I did some studio work, not a lot. It was a lot of pressure and it really didnít have anything to do with the kind of music I wanted to play.

L.A. is a tough town. One day you played a wedding, the next day you played a scab demo date, the next day you played a little jazz gig for 35 dollars and sometimes you played on a movie for a lot of money.

So I got sick of that. I was making good money, but I wasnít playing any jazz. So I got disgusted, saved some money, moved back to Philly and just decided that Iím only gonna play jazz. Iím not going to play weddings. Iím not gonna take any bad gigs, and if I had to I would take a day gig for a while, and I did. I tended bar for 2 years. And it paid off. I wish somebody in school would have told me that.

If you have some kind of goal or a dream, you have to just stick to it and donít let yourself get sidetracked. There are so many good musicians who get sidetracked. You never consider "what else can I do" so you donít get sucked into working weddings or other rotten jobs. Growing up, if I saw somebody who had a day gig, well he wasnít a good musician because he was just a weekend player. I grew up with that and it took a long time to get over that vibe.

TB: Whatís the worst gig you ever had?

JB: Wow. There were a lot of them. I donít know which one to pick! That would really be hard to say because there were so many bad ones, but I think working for Liberace would have to be one of the all time lows. We would sit behind the stage in Vegas and Iím playing the Beer Barrel Polka on the banjo. The music was just as far away from what I wanted to do as possible. That took a really bad mental toll.

TB: How do you judge what is good in music?

JB: I think the true test of what is good is if you last Ė if the person lasts or if the music lasts, which is something you canít know right away. But more on the inside part of that question, can the guy play his instrument well? Thereís a lot of players that can play their instrument but I may not like their music. The other thing, is it different or creative? Does it have any roots in tradition? Something thatís really good needs to have some kind of roots in tradition because nobody can just invent a new kind of music. Music needs to have some kind of connection to roots because music needs to grow. If you look at all the classical music, all the periods and changes that happened, they always took something from what was before.

TB: What is your opinion of jazz critics?

JB: Well, I like them when they say good stuff about me, but then when they donít like me I say "Itís just a critic." (Laughter) Iím being honest. Itís the truth. Everybody says "It doesnít bother me." But I think theyíre all full of shit. Everybody loves it when the critic says "Thatís the greatest thing I ever heard" and I think it bothers everybody when the critic says "Well, you knowÖ." I think thatís human nature.

TB: To what do you attribute where you have gotten today?

JB: It all happened when I decided that this is what I was going to do Ė that I was only going to do this. Thatís what I attribute it to. You have to be able to play, but I think the desire is half the battle, and then you have to put it in action. I used to walk around thinking I really want to be a jazz guitar player. And there I was Ė I spent half my life not playing jazz, just to make a buck. I used to wonder all the time "Why canít I?" -- well itís because I wasnít doing it.

It takes some sacrifice. If thatís what you want to do, play jazz guitar or sculpt peopleís faces out of marble, or whatever you want to do, at some point in your life you have to say this is what I want to do and you have to go do it. Nobodyís going to come over and say "Poof! Hereís $10,000. Go make records." I used to hope for that, but that was being totally unrealistic. Thatís what made it happen Ė when I stopped playing all the rotten jobs and only when I played what I wanted to play. Thatís when it happened.

TB: And it is finally happening for you.

JB: Little by little. When I lived in L.A., Guitar Player magazine would come out and that would be the shit. That was as hot as it could get. And in the October issue of Guitar Player, I have a full page write up by Jim Ferguson. Too bad the magazine is not jazz oriented at all anymore, but better late than never. It's funny, the month before, I got into JazzTimes and I was really happy with that but I wasn't as thrilled as Guitar Player. Guitar Player has like heavy metal guys in it now.

TB: Next to you is probably a picture of some guy with a bone in his nose.

JB: Yeah. But, sad to say, I was more thrilled by that than the Jazz Times. (Laughter)

TB: Spoken like a true guitar player.

© 2002 - 2016, Tim Berens

All rights reserved