|

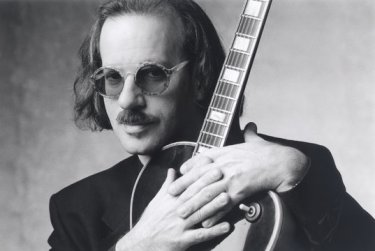

Joshua Breakstone |

Bio

Guitarist

Arranger

Conductor

Listen

Gallery

Fun Stuff

Contact

Originally published in the September, 1996 issue of the newsletter of the Cincinnati Jazz Guitar Society.

A conversation with Joshua Breakstone is like a visit to an art museum, a video arcade, a library and a counter-culture cafe that all share the same building. He's thoughtful, irreverent, clever, rebellious, intelligent and a joker.

|

|

Joshua Breakstone |

Like most guitar players who came of age after 1960, Joshua began his music career playing rock and roll. His first band consisted of flute, organ, bass, drums and guitar, and his interest in playing at that point was mostly centered on the social aspects of being in a band.

Joshua left high-school early, and began college at age 17. After receiving his Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in Jazz Studies at age 20, he began study for a Master's Degree in Music Education, which he completed at age 21. It was during college that he began to love and learn jazz.

Joshua's first recording was released in 1983, and since then he has released a total of 11 recordings as a leader and played on 2 more as a sideman. Four of Joshua's recordings reached the number one position on the Gavin Air Play charts.

The signature characteristics of Joshua's playing style are melodic inventiveness, fluid, horn-like lines, and harmonies etched by careful note selection.

TB: What was the first jazz record that made you go "Wow!"?

JB: The first time I remember hearing jazz and really loving it was when I heard Lee Morgan's "Search for a New Land." The thing that made me want to listen to the music was the fire of Lee Morgan's playing. I heard that and I was going "wow. This is exciting. It's interesting. It's thrilling." It's ironic that on that record Grant Green plays and at that time I thought "Man this guy can't play at all." I was not interested in the guitar whatsoever. It wasn't for many years that I came to understand jazz beyond the level of thrilling and exciting. It took years to come to a deeper understanding of exactly what it is we're doing when we're playing jazz.

Now I understand that the ultimate in jazz is to say something in a unique manner, to say something in your own way, to express something and to express something in your own way. It sounds like a simple thing, but it's really the highest achievement in jazz. In terms of that being the ultimate, Grant did it, and he's one of the few people who really have achieved their own language and their own style.

TB: What was your next move in listening?

JB: I went through lots of little love affairs with different musicians and music. There was a long one with Charlie Parker, with Dexter Gordon, with Art Farmer, with Lee Konitz, with Frank Strosier, with Barry Harris, and there were others. Of course being in New York was a huge advantage. When I started getting interested in jazz, we could listen to records of our favorite musicians and then we could follow them around town. I fell in love with Barry Harris' music and then I and my friends would go and listen to Barry Harris every Sunday at Bradlee's. We referred to that as church.

I loved Art Farmer and I went down to Boomer's and heard Art Farmer every night for a week. The rhythm section there for years was Cedar Walton, Sam Jones and Billy Higgins, so I became very familiar with each one of those great musicians.

TB: Usually when I'm talking to guitar players and I ask them who they listen to, they spit out the list of guitar players that they listen to. I notice how few guitar players there are on your list of early influences.

JB: Yeah. Especially early, I did not listen to guitar players. The only guys I had any interaction with on records in the beginning were Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell. I wasn't a terribly big Wes fan. I preferred Kenny Burrell. I've never listened to a lot of guitar. There was a time when I paid a great deal of attention to Pat Martino. In terms of music I've always preferred horn players.

TB: That shows in your playing. That's not meant as good or bad, but your licks and phrasing sound more horn like than guitar like.

JB: When I was doing my first recordings, I would get the comment from every side, constantly, all the time "Sounds like Jimmy Raney." "Obviously listens to a lot of Jimmy Raney". Everybody said "Jimmy Raney". And I had never heard Jimmy Raney. I had to go buy Jimmy Raney records. And when I heard the Jimmy Raney records I heard what they were talking about. It was an interesting experience for me.

I've been doing a lot of clinics over the last few years. One of the clinics that I like to do is entitled getting away from the guitar. What that means is, I don't want to see my students or young guitarists becoming great guitarists. OK?

TB: You don't want them stealing your record dates?

JB: (laughter) No! No! No! I don't want them to become these guitar people. My point is that we don't spend our lives devoted to learning about harmony, learning about melody, learning to master our instruments, learning our instruments, to stop there. I tell people that what they need to do is make that next step. To go from the level of improvisers to the level of artists who have something unique, who can come up with melodies of their own. In that sense, we have to get away from the world of the guitar, the world of guitar players and into the realm of sound, of music, of developing strong melodies, of being able to say things, of being able to phrase, which is a challenge for guitar players.

TB: Do you think that's something that can be taught?

JB: Definitely. The expressive elements of music are exactly the same as the expressive elements of speech. The dynamics of the voice are the same dynamics that one has to get into one's music, to be able to communicate. How we combine these dynamics is a matter of individual choice. These expressive elements are there in all of the great musicians' playing naturally. However, we mere mortals, aside from Bird and Hawk and all of these people, we mere mortals have to work to make our playing expressive and to use these elements that come so naturally to these great players in our playing.

These dynamics that I'm talking about are very simple. Just like you're listening to my voice now and you can hear my voice goes up. Well there's a natural balance that you know the next phrase my voice comes down. If I make a point my voice goes down, you know it is going to come back up. We do these things without thinking. This stuff is natural to us with speech, but we do not do it naturally when it comes to music.

It can be taught. There are two sides. There is the question of teaching improvisation, and the thing to keep in mind is that improvisation is nothing but a craft. I could teach anybody to improvise. It's a craft. It can be learned. There's nothing to it. The next step is the step that is interesting and is demanding, and where students have to dig and go farther. That is going from the level of improvisation or a craft and going to the level of expression or art.

TB: Do you see expression and art being inextricably tied to each other?

JB: To me, art is expression. Art in any of the various media is about saying something unique, about expressing yourself.

TB: It's been my thinking lately that that's not necessarily the case. You listen to the music of Bach and you don't get a feeling of Bach's self expression out of it, yet it is undoubtedly art of the highest caliber. I often wonder if some of the time, when you hear a player expressing himself, the expression gets in the way of the music because you are getting too much of the player's self, and you hear the ego of the person. Rather than a creation of art you see a simple self expression and quite often the expression is boring or self aggrandizing.

JB: I agree with you and disagree with you. You have to remember that in Bach's time, music was written in service to the Lord and it was considered blasphemous for anybody to have any sort of ego involved whatsoever. Now, as music has become more intensely personal and humanized, it became more interesting for me, in any case. As far as ego goes, I'm not talking about somebody stomping around on a stage and doing a show and all of that. I'm not pronouncing that as art.

Jazz has away been an art of individual expression. It's an interesting music, because you have individual soloists. But also, jazz has always been and will always be a music of group improvisation. You can't let your ego go beyond the bounds of being able to play within the group. So you do have a sort of natural boundary for ego. If you don't have that - if you end up imagining while you're playing jazz that you are in some situation where you are THE soloist, THE star, then jazz ceases to exist as far as I'm concerned.

TB: Painfully enough you do see that.

JB: You see that all the time.

TB: For me one of the most annoying things you see when you go to hear jazz is self indulgence. You don't see it quite so much in classical music, because the notes are all written down. When you get to the end of the notes, you stop playing. But when listening to jazz, we've all seen players get lost on ego trips while playing tunes.

JB: If the music is played correctly, it is group improvisation, so it is ego trip limiting in and of itself. There's a problem that people have become more oriented toward this ego trip stuff. I don't know if it's because jazz kind of lost its group aspects. Playing as a group or a unit is practiced by a very small clique of musicians. It is not prevalent in the world of jazz now.

If the music is being played right, it's all for one and one for all, like the Three Musketeers. Everybody is devoted to the cause of backing each other up. If you go out on the road and you're working with a quartet, if there's one guy out of the four that doesn't understand what it's about, then it can't really happen. You can make it happen. You can do a good imitation. You can put your best foot forward. You can do your best, but the real music is not going to happen.

Somebody like myself who probably plays 200 nights a year, if you get, and this sounds awfully depressing but I really think it's true, but if you get 20 or 25 out of 200 that are the real thing, you're doing OK. Maybe I could be a little more optimistic than that. I think this is a real problem for the music.

TB: Have you ever played the wedding scene and the casual gigs scene?

JB; Never. I have never done it. In my life, I have probably done 5 club dates. I've been lucky but, also I had an attitude when I was younger that I'd rather starve than cop out. I lived in some funky apartments for a long time with some cheap rents. But I wanted to go in just this one way and really be honest towards those kinds of goals. I have done weddings and parties that have been jazz weddings where I could play the way I play.

TB: But you haven't ever played the Hokey Pokey?

JB: Never.

TB: So, if somebody called the Hokey Pokey on a gig you wouldn't know how to play it?

JB: (Laughs) Well, no I would not be able to go "The Hokey Pokey," bam and just play it. But I could think well the Hokey Pokey goes like this and get through it. I've been lucky. I've struggled to keep things together and play and do things on my own. I got in with some very good musicians when I was very young and they were extremely encouraging and extremely tolerant people.

TB: Do you like getting thrown into a situation where you are the sideman, where you mold your playing to the leader's musical vision?

JB: I think I'm a terrible sideman. (laughter) I definitely prefer to be a leader. For me the ultimate thing is to be able to play the songs that I love, things that I really like to play, when I feel like playing them.

I marvel at how there are so many great players around the world who can take the music that I put down for them to play and sit down and make it sound sensational. I don't know if I have the capacity to do that, yet. I certainly do my best, but I hold sidemen, people who can make somebody's tune selections, make somebody's charts, make somebody's approach sound fantastic, I really admire people who do that all the time.

TB: When you travel, do you take a book of tunes with you?

JB: Yes, I do.

TB: I guess you must regularly call tunes that you expect they are not going to know? Do you call originals or old tunes outside the realm of the several hundred standards that everybody generally knows?

JB: I never know what people are going to know or that they're not going to know. Something that I've always told people in situations like clinics is that no matter how great "I'll Remember April" or "Stardust" are as melodies, we have an obligation as artists to play things we really believe in, that are meaningful to us, that we can really say something on, that we think are beautiful. We are supposed to be bringing music that is meaningful to us to people, showing them why this is beautiful, letting them experience that beauty too. So I look all over the place for music that I love. Some of it comes from non-traditional jazz places, some of it from originals of jazz musicians that are not as well known.

TB: I've heard stories about well known jazz musicians berating rhythm sections. How far do you like to go when making comments to a rhythm section that you are unfamiliar with?

JB: I almost never do. I don't feel like when you are in public, that this is a time to make this a teaching situation, so I will play with the rhythm section, and I will expect everyone to be playing their utmost, and doing their best, and if everybody is doing that, I'm not out there doing that. Sometimes I will make a minor comment to a bass player [on a break], like maybe you should think about coming down just a little bit. Just a little suggestion is the most I would make to somebody.

I can only recall 2 times in my life when I had to say something to somebody publicly. One was a bass player in London at a very well know club in London who made a racial comment about some people who came into the club and continued on and on and finally I just, I had lost it with this guy and I turned around to this guy and I said "I tell you what. You can get the . . . " [Editor's Note: Due to the colorful adjectives, the rest of this story has been censored. The basic gist is that Joshua demanded that the bass player leave the club immediately. Had the bass player followed all of Joshua's suggestions, the bass player would have required the services of a proctologist.] So there you go. Either I say nothing or . . (laughs)

TB: One last question for you, how do you travel with your L5?

JB: I have a soft bag that I use that enables it to get onto the airplanes, and it makes it easy for me to carry. I can stick it over my shoulder and have 2 hands free. I couldn't live without it. It's a very sought after item from Manny's.

© 2002 - 2016, Tim Berens

All rights reserved